The following article is based on a talk given by Didi Devapriya Deshaies (president of AEN) during the panel discussion: “How can we transform our educational system to help construct a compassionate and more livable future?” July 11th, AB Tech Campus, Asheville, NC:

Since last year, I have been part of a project in Bucharest to train 100 kindergarten teachers in the “We all Have a Story Project”, which was designed to awaken positive attitudes towards diversity in both teachers and kindergarten children. The project is financed by the EEA Grants in the “NGO Fund” program and is is a partnership between the Centre for Partnership and Equality (CPE), AMURTEL Romania and Romano Butiq.

During one of the training sessions, we led a simple exercise. The teachers gathered in a circle, and while their eyes were closed, we placed colored post-it notes on their heads. Most received yellow post-it notes while just a few of them received green ones. When they opened their eyes, they could see the post-it notes on the heads of the others, but they could not see their own. At first they just walked through the room, greeting each other and giggling at the oddness of having something stuck to their head. However, we then told them to avoid those wearing green postit notes as they were not their friends. The change in the atmosphere of the room was palpable and a certain tension began rising. As everyone began to ignore and exclude those with green, the giggling took on a nervous quality, as nobody was really sure what color they themselves had. Eye contact became insecure, and the question “are the others excluding me?” was hanging in the air.

During one of the training sessions, we led a simple exercise. The teachers gathered in a circle, and while their eyes were closed, we placed colored post-it notes on their heads. Most received yellow post-it notes while just a few of them received green ones. When they opened their eyes, they could see the post-it notes on the heads of the others, but they could not see their own. At first they just walked through the room, greeting each other and giggling at the oddness of having something stuck to their head. However, we then told them to avoid those wearing green postit notes as they were not their friends. The change in the atmosphere of the room was palpable and a certain tension began rising. As everyone began to ignore and exclude those with green, the giggling took on a nervous quality, as nobody was really sure what color they themselves had. Eye contact became insecure, and the question “are the others excluding me?” was hanging in the air.

Safety drops when exclusion starts operating

When we processed the exercise, the teachers reported how the minute exclusion began, everyone began to feel less safe. Sometimes we also asked those that had done the excluding why they did so – they replied, “because you told us to!”. Of course, this was indeed the case, but we asked them, why did you follow such instructions that were clearly hurtful and wrong? Even those who had been friends with someone in the outgroup for years, immediately began excluding them according to the instructions, to the surprise and shock of their friend,. There were a few exceptions – the one I remember the best was when one of the “greens” was a girl with a Roma minority background. She refused to be excluded and burst into the center of the circle where they had gathered to sing without the greens, and danced in the middle! Of course, it was a completely arbitrary and artificial situation, yet it gave cause to pause and reflect.

Children observe the powerful adult world

Are the social barriers that form between human beings, in reality, any less arbitrary and artificial? We learn them at such a young age, from observation of the powerful, authoritative adult world. It is an unfortunate reality that some children actually receive direct instructions from their families not to play with certain categories of children. But even when prejudice isn’t explicity spelled out, we notice right away, as small children, who is important and who isn’t important – in our school, in the subtle and not-so-subtle cues of the media, our friends, our families. Who is visible, and even in the spotlights of society and who is invisible? If our own experiences coincide with those that are given prestige and attention in our society our own sense of importance is reinforced, perhaps even overly-inflated. And yet, if our own experiences of ourselves, our abilities, our families are invisible, we may grow up with a sense that there is something less valuable, or even wrong about our own identity.

Inclusion is not just a “minority” issue, it affects all of us. Inclusion isn’t the same as simply being in social contact with a diversity of people. (SLIDE) Our greens and yellows were together, but the environment was one of groupism. To move towards a truly compassionate and livable future, we need to all fully embrace and champion an inclusive, broad vision of society, based on empathy. Empathy is the natural language of the heart. Prejudice, stereotyping and all forms of exclusion are learned from the outside. They are the result of our conditioning and adaptation to a world that is still dominated by competition and exclusion rather than cooperation and inclusion. When educational systems emphasizes learning from authoritative sources, rather than awakening processes of critical inquiry, biases are easily transmitted across generations. We cannot protect children from the harsh realities of the biased world, only by talking to them about love and kindness. If we want to inoculate them against the diseases of bias, exclusion etc. we must help them to think with their hearts. We must support the formation of a strong sense of justice, equality and love that is able to question irrationality, injustice and hurtfulness, even if it comes from the powerful authority sources of the grown-up world.

Inclusion is not just a “minority” issue, it affects all of us. Inclusion isn’t the same as simply being in social contact with a diversity of people. (SLIDE) Our greens and yellows were together, but the environment was one of groupism. To move towards a truly compassionate and livable future, we need to all fully embrace and champion an inclusive, broad vision of society, based on empathy. Empathy is the natural language of the heart. Prejudice, stereotyping and all forms of exclusion are learned from the outside. They are the result of our conditioning and adaptation to a world that is still dominated by competition and exclusion rather than cooperation and inclusion. When educational systems emphasizes learning from authoritative sources, rather than awakening processes of critical inquiry, biases are easily transmitted across generations. We cannot protect children from the harsh realities of the biased world, only by talking to them about love and kindness. If we want to inoculate them against the diseases of bias, exclusion etc. we must help them to think with their hearts. We must support the formation of a strong sense of justice, equality and love that is able to question irrationality, injustice and hurtfulness, even if it comes from the powerful authority sources of the grown-up world.

Addressing Roma exclusion in our kindergarten

I will share with you an example, that was actually the inspiration for the “We all have a story project” in Bucharest. In Europe, one of the most chronically marginalized and excluded minorities is the Roma population. When I was a small child, I remember dressing up for Halloween as a “gypsy” with big earrings, a long skirt and a colorful bandanna. Yet I had no idea that “gypsies” were an ethnic minority, and not just a lifestyle choice, until I arrived in Europe. The Roma population migrated from India more than a thousand years ago, during the extremely xenophobic middle ages where they were treated with widespread fear and hostility. In some cases, including Romania, they were enslaved, which is why there is to this day such a high proportion of settled Roma in Romania. Besides the Jewish population, the Roma were the other main ethnic minority targeted during the European Holocaust and annihalated in mass numbers.

I will share with you an example, that was actually the inspiration for the “We all have a story project” in Bucharest. In Europe, one of the most chronically marginalized and excluded minorities is the Roma population. When I was a small child, I remember dressing up for Halloween as a “gypsy” with big earrings, a long skirt and a colorful bandanna. Yet I had no idea that “gypsies” were an ethnic minority, and not just a lifestyle choice, until I arrived in Europe. The Roma population migrated from India more than a thousand years ago, during the extremely xenophobic middle ages where they were treated with widespread fear and hostility. In some cases, including Romania, they were enslaved, which is why there is to this day such a high proportion of settled Roma in Romania. Besides the Jewish population, the Roma were the other main ethnic minority targeted during the European Holocaust and annihalated in mass numbers.

I remember discussing once with some teachers when preparing to introduce a new curriculum theme about minorities. Our kindergarten has a long tradition of promoting the inclusion of children with disabilities, and we were exploring how to extend this inclusive attitude towards other minorities. One teacher said, “but in Romania we are not racist like you Americans. We are okay with black people.” I was quite surprised, and I asked her, “but what about the Roma?” She immediately replied “Oh that’s different, they are really bad, you cannot trust them.” Yet everything she was telling me was characteristic of the Roma as a people, from my point of view, were simply the characteristics of any group of people that is socially and economically marginalized and living in a rather bleak and hopeless situation.

A stereotype breaker joins the team

Soon after that, I hired, Iulia, a Roma woman into our organization as the executive director for our NGO. She was smart, educated and very capable. She was also a dedicated Roma activist. I was thrilled to have her in our team, and in a leadership position as she was the perfect stereotype breaker, not only for the teachers, but also for the children we are raising at our children’s home, many of whom had a Roma ethnicity, but were very much in denial and ashamed of that part of their identity.

Introducing curriculum about the Roma in kindergarten

Once she was in the team, we included her in the planning of a curriculum unit about the Roma minority, as it was first necessary for our own teachers to be exposed to correct information about the Roma and to challenge their own stereotypes so that they would not pass them on to the children. After a couple weeks, in which the teachers had been talking to the children about Roma culture, telling stories with Roma characters etc, we invited Iulia directly into the classroom, to interact with the children. The teachers had been using the term “Roma” during the curriculum, which, indeed is the more correct term – however, in popular culture and the uglier, more prejudice laden word is “tigan”. To help ensure that the children were making the connection between “tigan” and “roma”, I asked the children if they have any friends that were “tigan”? Some did, many didn’t, some said they weren’t allowed to play with tigani. Iulia was sitting right next to me when I said, I have a very good friend who is “tiganca”. “Really who? ” they asked. I then introduced Iulia as being tiganca but that she prefers that we say “Roma”. Now, they already knew Iulia and had often played with her, but when I introduced her in this way, one of the little girls had a sudden, pre-programmed reaction and said “eww, yucky…”jumping back. Now, all of the children began to consult with each other, saying that all tigani are bad, they steal, they are dangerous – and of course confirming their information with that ultimate, unquestionable authority – the TV!

Once she was in the team, we included her in the planning of a curriculum unit about the Roma minority, as it was first necessary for our own teachers to be exposed to correct information about the Roma and to challenge their own stereotypes so that they would not pass them on to the children. After a couple weeks, in which the teachers had been talking to the children about Roma culture, telling stories with Roma characters etc, we invited Iulia directly into the classroom, to interact with the children. The teachers had been using the term “Roma” during the curriculum, which, indeed is the more correct term – however, in popular culture and the uglier, more prejudice laden word is “tigan”. To help ensure that the children were making the connection between “tigan” and “roma”, I asked the children if they have any friends that were “tigan”? Some did, many didn’t, some said they weren’t allowed to play with tigani. Iulia was sitting right next to me when I said, I have a very good friend who is “tiganca”. “Really who? ” they asked. I then introduced Iulia as being tiganca but that she prefers that we say “Roma”. Now, they already knew Iulia and had often played with her, but when I introduced her in this way, one of the little girls had a sudden, pre-programmed reaction and said “eww, yucky…”jumping back. Now, all of the children began to consult with each other, saying that all tigani are bad, they steal, they are dangerous – and of course confirming their information with that ultimate, unquestionable authority – the TV!

Beyond hushing-up

This was a critical moment. Had I reacted with fear, and said “Hush, that isn’t polite, we shouldn’t say that,” then the children would have perhaps learned that it isn’t nice to say such things, but they wouldn’t have learned that where their information was incorrect. Rather, the indirect message is, yes, you are right, but you shouldn’t say it because it isn’t polite.

This was a critical moment. Had I reacted with fear, and said “Hush, that isn’t polite, we shouldn’t say that,” then the children would have perhaps learned that it isn’t nice to say such things, but they wouldn’t have learned that where their information was incorrect. Rather, the indirect message is, yes, you are right, but you shouldn’t say it because it isn’t polite.

However, I was delighted, as it was a great opportunity to intervene in a positive way. The children were still young enough, that the prejudice was right on the surface, and they were exposing it to test it out and see if it was right or not. It was also clear that they had been observing carefully lots of information in their environment and were making logical conclusions based on this erroneous, biased information from authoritative sources.

Stimulating Critical Thinking

I then began a questioning process, to get them to activate their own thinking and connect it to their hearts. As they were claiming that all Roma steal because they saw it on TV, I asked them, “In Germany do you think that there are people that steal? Or the US? Have you ever seen it on TV?” They consulted amongst themselves and agreed that yes, there are certainly also theives in other countries. “Do all Germans or all Americans steal?” “No, of course not” they decided. “So are you sure that all Roma steal?” I asked. Now they were not as certain as they had been a few minutes earlier. I then shared with them my thinking, “I think that there may always be some good people and some bad people everywhere.” They thought about that. Then I directed them to start finding out more about Iulia who was with us and who was Roma, did they think that she steals? “No!” they said. Rather, they found out what her favorite games and colors were, and many found they had something in common. They saw pictures of her when she was little. It was easy, spontaneous and natural for them to connect with her in this way. Then I asked Iulia if anything made her sad when she was little. When she then told about how some of the children used to tease her and call her names because she was Roma, the children were horrified. We asked them what they would do if that happened to one of their friends, and all of them wanted to help. When we went to role-play it, nobody wanted to be the bully that was teasing her. A year later, when we were doing an evaluation of the previous year and the children were asked to draw what they remembered learning, several of the children drew pictures of Roma people and said that they “Learned to love Roma (tigani)”. It was a very satisfying, impactful intervention and we began developing it over the course of several years.

I then began a questioning process, to get them to activate their own thinking and connect it to their hearts. As they were claiming that all Roma steal because they saw it on TV, I asked them, “In Germany do you think that there are people that steal? Or the US? Have you ever seen it on TV?” They consulted amongst themselves and agreed that yes, there are certainly also theives in other countries. “Do all Germans or all Americans steal?” “No, of course not” they decided. “So are you sure that all Roma steal?” I asked. Now they were not as certain as they had been a few minutes earlier. I then shared with them my thinking, “I think that there may always be some good people and some bad people everywhere.” They thought about that. Then I directed them to start finding out more about Iulia who was with us and who was Roma, did they think that she steals? “No!” they said. Rather, they found out what her favorite games and colors were, and many found they had something in common. They saw pictures of her when she was little. It was easy, spontaneous and natural for them to connect with her in this way. Then I asked Iulia if anything made her sad when she was little. When she then told about how some of the children used to tease her and call her names because she was Roma, the children were horrified. We asked them what they would do if that happened to one of their friends, and all of them wanted to help. When we went to role-play it, nobody wanted to be the bully that was teasing her. A year later, when we were doing an evaluation of the previous year and the children were asked to draw what they remembered learning, several of the children drew pictures of Roma people and said that they “Learned to love Roma (tigani)”. It was a very satisfying, impactful intervention and we began developing it over the course of several years.

Prejudice not yet crystallized in the early years

In 2014 we formed a partnership with two other human rights organizations

In 2014 we formed a partnership with two other human rights organizations

in Bucharest, CPE and Romano Butiq, to share and further develop this methodology for promoting inclusion; not only of the Roma, but also of children with special needs and to overcome limiting gender stereotyping. We chose to focus on the early years, as this is the key period when children are forming their basic belief system about the world and others. At this stage, children are still making hypothesis

and testing them out, but later, if biased information is not challenged with more rational, correct information, biases are internalized and crystallize as a more rigid part of the child’s worldview that can be difficult to “undo.” As the founder of NHE said, a bamboo can be easily shaped when tender and green, but once it dries and hardens, it breaks when bent. Children that are appropriately exposed to positive experiences of diversity, accept diversity easily and naturally and do not have to work as hard to deconstruct bias and prejudice as adults that did not have such experiences.

Authentic relationships are key

Authentic relationships are key

The basic premise of the project, is that one of the best antidotes to prejudices is authentic friendship. I also believe that one of the best ways to foster respect, friendship and understanding between people is to listen to each others stories. When we can create safe contexts, in which people are able to open up and share their human experiences, we are easily able to connect and relate to them. We see the universal beauty of the human being. We often discover we have so much more in common than different and the differences become something interesting, rather than threatening. We have the chance to be curious, and to find out more. Many times, we may sense barriers formed by what we think is “politeness”, but when we feel safe enough to be open, we discover that even those barriers are just another expression of fear and ignorance, and they have a chance to dissolve into nothingness, as they are baseless. Once you know someone well enough to care about them, who is gay, or deaf, or from another ethnicity than you – it is hard to continue making negative generalities about the whole group, because you will think about your friend. Even here, we have to be careful, because some people manage to make an “exception” out of their friend and still hold onto the stereotyped image, saying “oh, but you are not like them, you are one of us.” We made sure to sensitize our teachers to how such thinking puts the minority person in an even more uncomfortable situation and double bind of having to participate in the rejection and exclusion of an important part of their identity and their own group.

Getting to know each other by asking questions

I remember introducing a Vanja, a Buglarian woman with visual disabilities to the children of our “Familia AMURTEL” children’s home. I encouraged them to ask questions how she managed different daily situations. For example, they asked – “How do you know if your clothes are matching if you can’t see them?” It was fascinating to find out all of the creative solutions she had worked out. She said, “You see – I can do everything you can do.” and I added with admiration and respect “Yes, you certainly can, just you work harder and with more creativity.” She smiled and agreed.

Falling in love is natural

I believe that if we can truly see another human being, we will fall in love with him or her. This is our natural relationship, it is nothing special or extraordinary to fall in love, it is how we would feel about everyone if our hearts were truly awakened. So, in our project, one of the core components of the project, was to include the opportunity for the teachers to meet a wide variety of real people, from minorities and with special needs and to facilitate sharing personal experiences and stories. It was a satisfying success. Though we had already led other trainings to sensitize the teachers to the experiences of minorities – nothing is as memorable and eloquent as when another human being opens up and shares their own, personal experience with you. During that same session, I helped the participants to learn how to share specific experiences from their lives in an interesting, age appropriate manner with children. One of the young men that participated, who has visual disabilities since birth, for example, described his friendship with a favorite uncle, and how they used to walk through the village, exploring it through different smells, sounds and textures – from the unpleasant smells of a house with pigs that hadn’t cleaned out their sty in some time, to the delicious scent of baking bread coming from the house of a neighbor, and the muddy texture of the unpaved road, the sound of horse carts, etc. The teachers were moved, and our guests were inspired and empowered. The next step of the project, this autumn, will be to have the teachers invite the resource people they met directly into the classroom, and facilitate them to share their stories. The teachers will also facilitate the children to interact with them, as well as to work through any prejudices that arise in a rational manner, as I described in my experience with Iulia.

I believe that if we can truly see another human being, we will fall in love with him or her. This is our natural relationship, it is nothing special or extraordinary to fall in love, it is how we would feel about everyone if our hearts were truly awakened. So, in our project, one of the core components of the project, was to include the opportunity for the teachers to meet a wide variety of real people, from minorities and with special needs and to facilitate sharing personal experiences and stories. It was a satisfying success. Though we had already led other trainings to sensitize the teachers to the experiences of minorities – nothing is as memorable and eloquent as when another human being opens up and shares their own, personal experience with you. During that same session, I helped the participants to learn how to share specific experiences from their lives in an interesting, age appropriate manner with children. One of the young men that participated, who has visual disabilities since birth, for example, described his friendship with a favorite uncle, and how they used to walk through the village, exploring it through different smells, sounds and textures – from the unpleasant smells of a house with pigs that hadn’t cleaned out their sty in some time, to the delicious scent of baking bread coming from the house of a neighbor, and the muddy texture of the unpaved road, the sound of horse carts, etc. The teachers were moved, and our guests were inspired and empowered. The next step of the project, this autumn, will be to have the teachers invite the resource people they met directly into the classroom, and facilitate them to share their stories. The teachers will also facilitate the children to interact with them, as well as to work through any prejudices that arise in a rational manner, as I described in my experience with Iulia.

We are here today because we all believe in creating a compassionate and livable future. This is the same dream that has been helping humanity to slowly evolve, like a pole star that we use to keep recorrecting our course. For hundreds of years, visionaries have tried to inspire us towards a more peaceful future based on values of love. However, vision and ideals alone are not enough. The evolution of consciousness is a process and one that requires our active participation. We need to also have a clear understanding of the dynamics that obstacle this positive evolution. If it is natural to empathize, to love, as I mentioned earlier – why does the world present us with so much evidence of hatred, aggression, war, violence and exclusion?

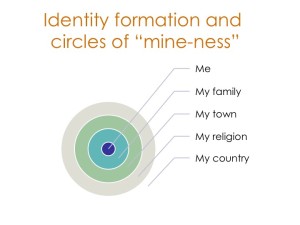

If we look at the formation of our identity, it begins of course with a sense of our own self. We then learn to identify with our family and everything within this circle is safe, while the rest of the world is Other. We first step out into the greater world by going to school, making friends from our neighborhood. We later will form a sense of belonging to a particular city or state, religion, country, gender, etc. We form a sense of identity with many layers, like concentric circles. Everything within these circles or comfort zones is ours, is like “me” – yet this sense of “us” generates a sense of a “them”. The self and the Other, us and them. When the “Other” is not part of Us – it is part of an unknown, it is alien, perhaps even dangerous.

If we look at the formation of our identity, it begins of course with a sense of our own self. We then learn to identify with our family and everything within this circle is safe, while the rest of the world is Other. We first step out into the greater world by going to school, making friends from our neighborhood. We later will form a sense of belonging to a particular city or state, religion, country, gender, etc. We form a sense of identity with many layers, like concentric circles. Everything within these circles or comfort zones is ours, is like “me” – yet this sense of “us” generates a sense of a “them”. The self and the Other, us and them. When the “Other” is not part of Us – it is part of an unknown, it is alien, perhaps even dangerous.  When the “other” is experienced as “not self” it generates fear. Behind the phenonmen of exclusion, hatred, violence, etc. I believe you will find different expressions of fear of the other. P.R. Sarkar, the founder of Neohumanist education and philosophy, talked about the need to expand this radius and rather than creating fear-generating barriers – to keep expanding our sense of identity and empathy

When the “other” is experienced as “not self” it generates fear. Behind the phenonmen of exclusion, hatred, violence, etc. I believe you will find different expressions of fear of the other. P.R. Sarkar, the founder of Neohumanist education and philosophy, talked about the need to expand this radius and rather than creating fear-generating barriers – to keep expanding our sense of identity and empathy

until we have the widest possible “circle” – A circle that includes the whole universe. A circle without limits. This would not erase our individual identities – we cannot and shouldn’t try to standardize our identities – rather “diversity is the law of nature” and can be celebrated and enjoyed.

The only way to overcome fear, is to face it and realize it is baseless, groundless. While light has a physical existence, darkness does not – it is simply the absence of light. In the same way, while love has an existence, fear does not – it is simply a lack of love. So wherever we find a barrier, wherever there is that hesitation, that discomfort, shyness, or even more overtly hatreds or other barriers, we must challenge them. If we turn on the light, darkness immediately vanishes. If we allow ourselves to go beyond our comfort zones, and discover another human being, barriers of fear and ignorance evaporate and we find our humanity affirmed and empowered. To do so, requires taking an active stance, but the rewards are living a fuller, freer life. Fear, left unchallenged, will keep us safely in our comfort zones. As parents, teachers, or policy makers we cannot assume that we are free of bias, if we have not actively made efforts to challenge it and to step outside of our own comfort zones and allow ourselves to enter into the culture and world of another. Making this efforts however, will help us to have the courage to also help children to stay connected to their own hearts and safely expand their own circles towards a universal, neohumanist outlook. In this way, we can build a truly compassionate and livable future.

The only way to overcome fear, is to face it and realize it is baseless, groundless. While light has a physical existence, darkness does not – it is simply the absence of light. In the same way, while love has an existence, fear does not – it is simply a lack of love. So wherever we find a barrier, wherever there is that hesitation, that discomfort, shyness, or even more overtly hatreds or other barriers, we must challenge them. If we turn on the light, darkness immediately vanishes. If we allow ourselves to go beyond our comfort zones, and discover another human being, barriers of fear and ignorance evaporate and we find our humanity affirmed and empowered. To do so, requires taking an active stance, but the rewards are living a fuller, freer life. Fear, left unchallenged, will keep us safely in our comfort zones. As parents, teachers, or policy makers we cannot assume that we are free of bias, if we have not actively made efforts to challenge it and to step outside of our own comfort zones and allow ourselves to enter into the culture and world of another. Making this efforts however, will help us to have the courage to also help children to stay connected to their own hearts and safely expand their own circles towards a universal, neohumanist outlook. In this way, we can build a truly compassionate and livable future.